When Dr. Demetris Yannopoulos was studying medicine at the University of Athens in Greece, his passion for freediving sparked a lifelong exploration of how the human body responds to lack of oxygen. Decades later, he is a leading international researcher in resuscitation medicine whose work is changing resuscitation practices. Today, he is revolutionizing cardiac arrest care, producing impressive survival rates that have drawn the interest of medical institutions around the world.

Over the last seven years, Dr. Yannopoulos has transformed the use of ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation), a form of life support that takes over the functions of the heart and lungs, pumping and oxygenating the patient’s blood outside the body and allowing the heart and lungs to heal. After demonstrating initial success bringing cardiac arrest patients to the cath lab at University of Minnesota Medical Center for rapid placement on ECMO, Dr. Yannopoulos next worked with Helmsley to realize his vision of bringing ECPR (using ECMO to take over the heart and lungs) beyond the walls of a singular medical center.

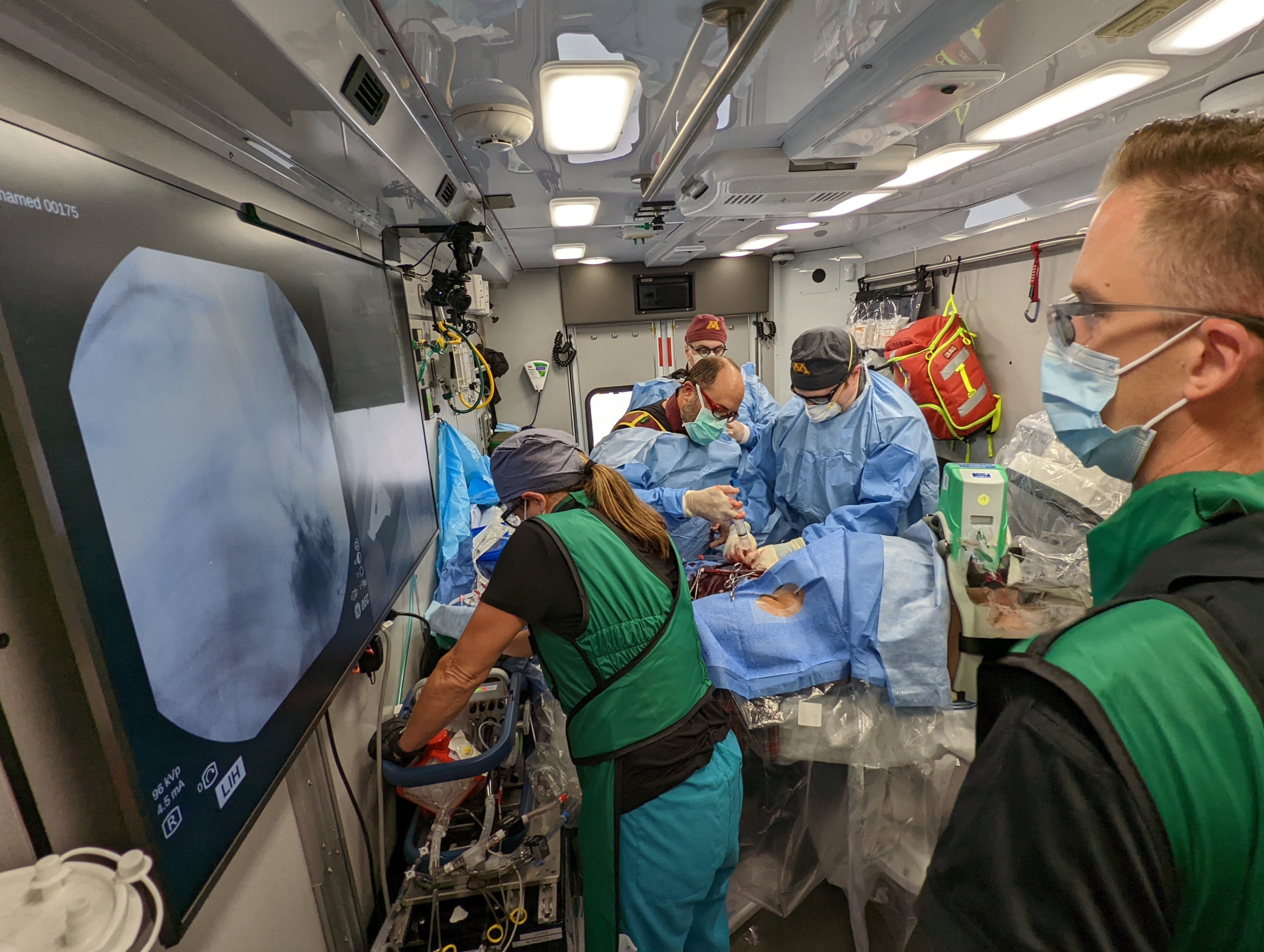

Backed by an $18 million investment from Helmsley, Dr. Yannopoulos and his team developed a rapid response protocol to quickly get patients on ECMO. The team also developed a truck that carries ECMO technology directly to a cardiac arrest patient, shortening the time that patients spend on CPR and increasing survival rates.

During the early stages of the project, this seminal work was validated with an unprecedented 43 percent survival rate for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients who underwent ECMO in the randomized controlled ARREST trial.

Dr. Yannopoulos recently sat down with Wayne Booze, a program officer with Helmsley’s Rural Healthcare Program, to discuss, for those are not yet familiar with ECMO, what limits resuscitation medicine faces, why ECMO is a game changer, and what the long-term potential is for this treatment.

Talk about our current challenges in resuscitation that spurred you to explore ECMO as a key part of care after cardiac arrest.

Resuscitation is the most time-sensitive emergency that exists, other than bleeding out to death. Every minute counts. Unfortunately, the ways that we have to deal with this are limited. CPR is only effective for 10 to 15 minutes. We cannot really do much other than trying to re-establish circulation and oxygenation. Every effort in cardiac arrest management is to try to bring the heart back.

You don’t have to be a physician to understand that the brain requires oxygen, and blood flow with oxygen is good. Even small periods of hypoxia in the brain can have detrimental effects, and CPR by itself cannot maintain forward blood flow with enough oxygen to maintain viability over long periods of time.

Over the last decade, ECMO—the ability of having a pump that can replicate the heart and the lungs, immediately and very efficiently—came to life. We started an ECMO program about five years ago. We started bringing people here, trying to understand, if they come late, when everything else has failed, can we still save some people? We were amazed that we could actually save some people that we initially thought were dead.

Because of ECMO, you have the potential to now reverse the cause of cardiac arrest and save somebody’s life. That is the fundamental core of all this.

Dr. Yannopoulos and his team working on a patient inside of the ECMO truck

Would you share how your resuscitation center use ECMO for cardiac arrest care, and what kind of results are your patients having?

Everything that we do is a strategy to minimize the time from cardiac arrest during which the patient receives CPR without being in a normal cardiac perfusion state.

We have a team, shared by six of seven major EMS agencies working in collaboration, that deploys to cardiac arrest patients. Based on the location, the timing, the day, we can deploy to the closest participating emergency department in one of three hospitals, deploy the ECMO truck, or bring people to the university cath lab. We are building, in this department, with the generosity of you guys, an ECMO-dedicated suite.

The outcomes depend a lot on how long it takes patients to come to us. For patients with an average CPR duration of about 55 minutes, we have a survival rate of about 35 to 40 percent, which is unheard of.

There is a big difference between 30 minutes of CPR—for which, if you cannulate on average in seven minutes, your survival should be close to 80 percent—and 40 minutes of CPR, for which your survival goes down to 60 percent. But still, 60 percent resuscitation rate and survival from people that received 40 minutes of CPR is unheard of. It doesn’t exist. In our randomized trial, for people that have 50 minutes of CPR only, they have a zero percent survival rate, versus 40 percent in the ECMO group.

But still, these survival rates are not good enough, at least for me. I think the numbers should be higher, and we can get higher only by interfering earlier. To make those improvements, we will also need to solve a technology development issue and a logistics, health system reorganization issue.

Would you talk a bit about how philanthropic support enabled you to develop this program?

When I met Walter [Panzirer] for the first time, I found a kindred spirit. What most impressed me about Walter was that he had significant interest in the resuscitation field, even though he was not an expert, and he immediately realized the potential of what we were proposing. That first day, we basically saw eye to eye.

Walter had the vision to believe in our work, in the things I proposed a long time ago, which, back then, seemed like science fiction, right? The good rapport that we had motivated me significantly to not let him down. When somebody says “I put my support behind you because I believe you,” you end up working harder to deliver.

The support from Helmsley has been the critical catalyst, the infrastructure support we needed to prove that a concept works. It’s very difficult to make change happen in this kind of complex environment without collateral, because this was not just a simple scientific idea—the simple scientific idea was answered in the ARREST trial.

We are restructuring a healthcare system, creating something completely outside the current delivery process. This can only happen via philanthropy. There’s no real incentive for any other organizational funding—NIH or NSF—to pay for that.

The biggest, most complicated thing that I appreciate Walter’s faith in—because I didn’t have a lot of faith—was the fact that we could bring together healthcare organizations and work together. Walter held conversations with stakeholders here in the university, in the healthcare system, and helped me pave the path to be successful.

That was not a scientific challenge. It was about managing competing entities for a common good, and that was only possible because we had the funds. We had the infrastructure to be able to say to healthcare organizations, “Listen, you don’t have to have anything out of your pocket. What we want is your commitment to do what we can for patients.” Once the results were published, and we showed that this could be done in their hospitals, then the organizations were on board.

Our relationship with Helmsley has been critical, in terms of Walter greasing the wheels of progress and being very, very supportive, even with crazy ideas that we had. Implementation of this community-wide ECMO program in order to bring it to bigger population bases was fundamentally accelerated by the understanding, commitment and generosity of the Helmsley organization. Without Helmsley’s initial support, that will never have happened. Wow. Thank you for that.

Helmsley Trustee Walter Panzirer and Dr. Yannopoulos outside the ECMO truck

Are other hospitals changing how they use ECMO because of the outcomes you’re having?

The work here has instigated a lot of new developments in LA, San Diego, New York, Boston to replicate our program. Baltimore City is coming together with my guidance to develop a joint program at Johns Hopkins and the University of Maryland, investigating how to go about collaborating rather than competing. A London team came here for about two weeks. A Chinese team will come tomorrow. We will have a team from Columbia and Weill Cornell in New York. And many more.

Right now the majority of hospitals with ECMO programs bring the patient to the hospital, so it’s an initial collaboration with EMS to identify people early, and then to activate a response team that is available 24/7 for an early cannulation in emergency departments. That by itself is always the first step.

Then hospitals need to figure out how to manage people in the hospital. That has two advantages: one, you save some people from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, and two, this opens up the in-hospital cardiac arrest population, which becomes now eligible for ECMO. Now they can treat in-house cardiac arrest in a better way than they were doing before.

The main focus here is developing the expertise. I’ve done 1000 ECMOs in the last seven years. What works? When do we go up? What flows do we use? It’s all stuff we didn’t know before. All these things focus on the development of the team, their expertise.

In the long run, where do you see potential for advancements in ECMO for ECPR?

We, as an organization and as a scientific community, have realized that bringing ECMO equipment on such short notice is impossible to do at scale. What we need to do is miniaturize the equipment and use intermediate steps to protect the brain with small cannulas or ECMO circuits that weigh no more than 15 pounds. This can be delivered by trained medics or EMS doctors.

The future looks like small machines and targeted automation of vital organs that will happen in the field. Perfuse the body with blood, and then you have enough oxygen to support the vital organs until you hit the hospital an hour later, when most of the systems by then have the ability to respond adequately.

What I do now and what we do as a group of people cannot be widely replicated—the technical aspects and the expertise. It will take too long to train the workforce. People don’t want to live my life—being on call every day and running around randomly and going from dinner to putting somebody on ECMO in 15 minutes. But if that’s your job for the day, and you don’t need to have this expertise and you don’t need the big truck, then you can do it.

We can save a lot of lives. You can apply ECMO to a lot of other indications, not only just the shockable cardiac rhythms. You can basically reach survival rates probably in the 70 to 80 percent range. My vision is that maybe I’ll achieve it before I retire or die. This life-saving procedure will be done widely in the United States and in all societies that can afford to use things like this, but also, as the technology becomes more widely available, ECMO can improve the lives of millions of people around the world.